HARS - High value information Alert and Reporting System

Brown Glove Bandit and Kilty

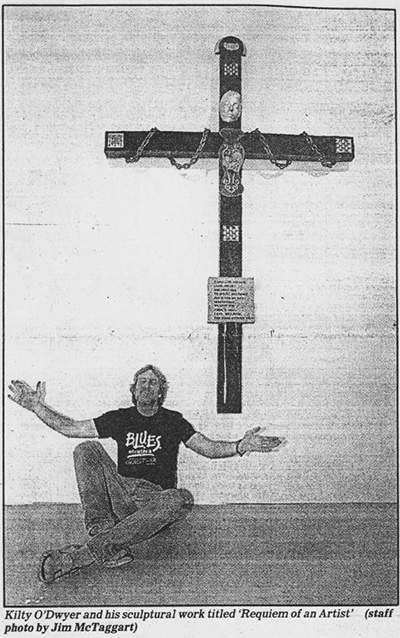

Restoring A Ruined Life Through Art

by Liz Seaton

special to The Star

Kansas City Star

September 18, 1989

Kilty O’Dwyer, aspiring artist and writer, says being homeless is like living in a black hole. A few months ago, he was without a home on the sidewalks of Tempe, Ariz.

His story is one of endless disappointments that have inspired him to produce intriguingly naïve and yet perceptive art work and writings. He says he wants to turn his sometimes desperate life experience into art.

“I mean, I was out on the streets,” he says. “Eating out of dumpsters, checking newspaper machines and telephones every morning for coffee money. I got real burnt out.”

He laughs a growling laugh from a throat worn by cigarettes and 47 years of experiences that he says have nearly sheared his trust in people and God. When speaking, he often refers to an abstract group of beings who are indifferent to his needs – a “them,” those in control, those who don’t understand.

With his red-blond hair and beard, freckled complexion and black T-shirt, he looks like Willie Nelson minus the bandanna. “People always tell me that, “ he says.

It took him 12 days to get to town from Tempe last May, walking and hitchhiking, trying to get people to trust him so he could get a ride. If his friends on the streets in Arizona saw what he was doing now, they wouldn’t believe it – living in his own space, doing odd jobs for money.

Writing poetry and making art. “This is my last hurrah, It’s do or die,” he says. “It’s going to work, because I’ve gotten rid of the things that weighed me down before and stopped me. There are no things now. There are no rules. I’m absolutely unlimited, unrestricted.”

He has had a job recently working at the Leedy-Voulkos Art Center Gallery, 2016 Baltimore Ave. Some of his own work was on display there this summer. The poems he has written over the years have found their way onto his sculptures. He says these are the first pieces he has done since the late 1970s, when he nearly completed a master’s degree in sculpture at Arizona State University.

One of his works is fashioned of smashed car parts covered in black tar – a fender, a hubcap, glass and rocks, all underneath the face of a windshield cracked in half. He has rigged one head-light to shine on the windshield. It reflects as two beams.

A poem, constructed in gold plastic letters, appears underneath the light: “… The forgotten days run away / But the future and I / Are running towards each other / Heading for shocking collision.”

If you look closely, O’Dwyer points out, you can see the dim image of a shiny new car in the windshield. Its headlights are menacing, like Stephen King’s “Christine.”

“That’s the future,” he says. The future looks forbidding to him. But anything looks better than the past.

He would rather tell his story over a glass of beer, he remarks, explaining that beer has been a form of sustenance for him. “Kept me healthy. It has a lot of protein. I’ve lived for weeks on peanuts and beer.” Since coming to Kansas City, he says he drinks less beer.

He describes his service in the Vietnam War and how five friends from his reconnaissance team died, not there, but back in the United States. “Three at the gun,” he says, “one was blown away in a robbery, the other on an icy road.”

After the war he married a woman from Japan, but he says his wife and child also were killed in an automobile accident. He married again and made money building swimming pools for a while in Illinois and Arizona. He started taking education courses in art at Arizona State.

Later, divorced, he camped alone in the mountains of Arizona for nine months. He spent two years on the streets of Tempe and several months working in the Holy Trinity Monastery of St. David. Those times with the Benedictines, he says were “soul-searching, decision-making” periods. Until recently he was living on the streets again in Arizona cities.

All the time he wrote fiction or poetry on scraps of paper, mostly legal pads, he says, leaving finished poems and stories with friends along the way.

He ends his oral autobiography and pulls out his poems carried in a wool Pierre Cardin briefcase he found on the Arizona State Campus.

Putting on this wire-rim glasses, he looks remarkably like a professor of literature. He is a born orator. He reads a few chosen pieces in his grumbling voice. The canter of his speech falls softly into an Irish brogue: “I walk slowly / Not because I’m tired / But because / No one’s waiting anywhere.”

O-Dwyer remarks that since his friends in Vietnam and members of his family have died, there have been few people to support him – few “waiting anywhere.” He regards people uncertainly, saying he’s not interested “in being responsible to anyone. I’m best when people leave me alone.”

He says, however, that he has become less isolated since meeting Larry Beuchel, a graduate of the Kansas City Art Institute, and Jim Leedy, a sculptor and professor at the Art Institute. Both were working in Tempe a spring ago and had contact with O’Dwyer.

Beuchel, who was working as a teaching assistant at Arizona State, says O’Dwyer came up to him at a bar to sell him a pair of sunglasses for $10.

“When I found Kilty in Arizona, he was really unhealthy,” the artist recalled recently efore leaving for Virginia to complete graduate studies. “He looked bad. He’s made a lot of progress. He’s doing new writing. He has some strong pieces. Now he has to learn how to choose which ones to read.”

Beuchel was attracted to the homeless man’s stories and poetry and decided to include O’Dwyer in an installation project set up in two abandoned houses that were to be razed by the city.

“The project was an attempt to give the houses on more life before they died,” Beuchel says. While he worked in one home on a piece with lights, his students from a course in three-dimensional design worked with O’Dwyer and several other people from the streets to construct a show in the rooms of the other dwelling. O’Dwyer filled the walls and ceiling of one room with his poetry. He took shelter in the space at night.

Leedy, who owns the warehouse and gallery in Kansas City where O’Dwyer now lives, was giving guest lectures at Arizona State and critiquing Beuchel’s project when he met O’Dwyer. He taped O’Dwyer’s readings along with stories from others living on the streets and included the recordings on a program he produces for KKFI-FM in Kansas City. He invited O’Dwyer to send more work to Kansas City as it was written.

“It’s good stuff,” Leedy says. “Even when Kilty was at his lowest point out there, he was writing. That was his release.”

Instead of sending poetry, O’Dwyer sent himself to Kansas City. It took him a year to get to town. “I almost didn’t come, because I was afraid. No one had ever believed in me before.”

Now he feels a renewed sense of direction. He credits his friends in Kansas City, and he credits himself. Somewhat metaphorically, he says those months living alone in the mountains of the Southwest left him feeling like the eagles he saw there – birds that symbolize what he believes is an unappreciated sense of freedom among humans, that fly in the sky with the determination to set records of height like Richard Bach’s Jonathan Livingston Seagull, one of his favorite fictional characters.

He concedes that his progress report still has some fine tuning. In his search to record his world through poetry and art, he says, he is still “finding the pieces,” insisting the greatest piece of all is “brotherly love.”

“I don’t know if we ever know the truth,” he says. “I think as go along you get pieces of it. What’s important is that you keep those pieces. Somewhere along the line, I would hope that you end up with all of them.”

EPILOG

I have told how I met Kilty, in a bar next to a Laundromat -- this was after his sojourn down town as revealed in the newspaper article above . I recall him telling me that the Missouri river had flooded, as it is prone to do every ten years or so, and some of the downtown area was inundated in the flood waters. The flooded area included the “art-houses”, and again, he was homeless and drifted to the outskirts of the city, where somehow he met the sadist with the BMW (No offense to BMW intended) who had a small house with a vacant, detached garage, which was Kilty’s home when I met him. That was about twenty years ago. Is it possible that Kilty O-Dwyer still is searching for his future somewhere, or perhaps he found it. If he hasn’t, please inform him that an old friend has an outstretched hand, and hopes he will grab a hold of it. Just contact this website for an alternate future Kilty.